ISSUE 15

Isobel Waller-Bridge On Listening Deeply, Moving Slowly, and Cultivating the Quiet

WORDS BY LOREN SUNDERLANDPHOTO BY CHLOE LE DREZENIt’s a grey January afternoon in London, and Isobel Waller-Bridge is sitting in her studio. The space - part of a bigger studio complex - has four skylights at the top, though she’s covered them. “There’s a tint coming through from a different piece of glass,” she explains. “So it’s kind of green, it feels like I’m in a David Fincher film!” she laughs. “Light can… It’s easier to lose yourself when you’re in the dark, I think. Or to disappear from yourself.”

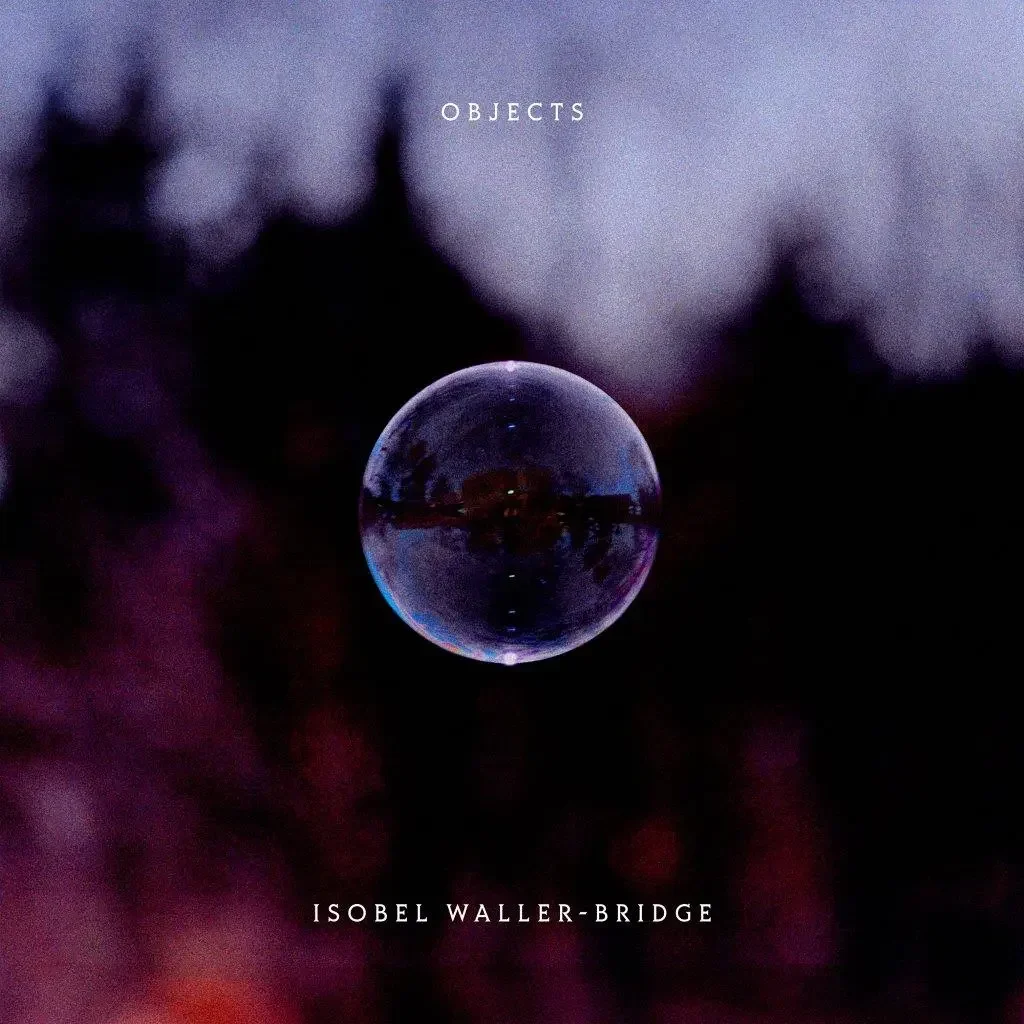

This is the composer behind some of the most affecting scores in recent memory, from Munich – Edge of War and Emma, to the textured atmospherics of Objects, her latest album released last year. She’s also known for work on Fleabag, Emma and Black Mirror, alongside commissions for ballet and fashion houses. Waller-Bridge has spent the last decade navigating the peculiar pressures of success, the noise from other people’s expectations, and the eternal question that plagues every artist: Am I being true to my own voice?

We’re speaking just days into the new year, both of us still shaking off the cobwebs of the Christmas break. She’s just returned from New York, where she spent time away to have some well-earned R&R. “It was the first time I ever spent it away from my whole family, which feels kind of insane”, she says. “I was like, I wonder if it’s going to be really lonely, just me and my partner, but it was so nice.” There’s a quietness to the way she speaks, as though she’s still figuring out what she thinks even as the words form. She describes herself as someone who listens more than talks, gravitating toward introverted creative spaces. It’s a trait that’s shaped not just how she works, but who she is as an artist.

“Being an introvert really helps composition for me,” she reflects. “I’ll be at a party or an event, I won’t be the one making all the noise. I’ll be a bit more watchful, maybe, just taking in the surroundings.” This quality of deep listening extends to her collaborations, too. “If somebody’s come to me, I really want to take the time to listen to them and get inside, really understand what the vision is and where they’ve started from.” She pauses. “If I’m hearing the sound of my own voice too much, something is wrong there!”

But when she’s alone (which can be most of the time for composers), something shifts. “The strange thing is that when I’m on my own, I do talk to myself quite a lot,” she says, laughing again. “If I’m scoring something and I don’t have the collaborator in the room, I’m then in a dialogue with the thing that I’m scoring. I’m listening to the environment that they’re in, the tonality of their voices, what they’re saying.” And when she’s working on her own music, like Objects? “The internal monologue becomes much louder because I’m not absorbing somebody else’s ideas all the time.”

Managing that internal criticism, the second voice, as she calls it, has become a huge part of Isobel’s practice. She walks a lot, too. “The walking around and the dreaming and the thinking is about 80% of it really,” she says. “Then it’s kind of intense writing sessions where I have to exhaust myself with long stretches of writing, completely on my own, so that I can get to that period of trance where I’m no longer really conscious of what I’m doing.”

An almost ritualistic creative process that she’s created for herself, she’ll turn off the lights and work only by lamplight. Her phone is on Do Not Disturb. She even uses a physical kitchen timer, setting it for 20-minute spurts followed by five-minute breaks. “Eventually, I don’t need to set it, I’m in the thing.” Everything is recorded, every improvisation and idea is captured, and then comes the painful part: “Having to go back and filter through everything and pick out the bits that are interesting.”

For her album, Objects, it felt like a statement of intent for the composer, or perhaps more accurately, a straight-up refusal. In a time where we’re all experiencing accelerated consumption, 15-second clips and algorithm-driven attention spans, Waller-Bridge made music that demanded that you slow down. Some tracks stretched past ten minutes; one originally ran to 20. “It really felt like no one was going to have the time to listen to this except for me,” she says. “No one was going to have the patience to listen to this.”

"I love it when somebody finds my music from a record rather than from a score."

But patience, for her, was the point. “To actually make it, that’s when I started to feel good about it, in that very process, I felt my internal rhythms were slowing down to really make me feel like there was more space in my own mind.” The music isn’t melodic in any conventional sense; it’s textural, abstract and requires your attention that borders on meditative. When we speak about finishing the record, Isobel shared that part in itself becomes an ordeal. “I struggle with finishing any project,” she confesses. “You have to really commit to those choices that you’ve made. The mix process I find challenging because you start to hear it in new ways, and somebody else may have a take on something that you’ve done.” And when Objects finally hit the digital and physical shelves? “On the day of releasing something, I delete all of my social media, and I almost want to ignore that it’s happening! Then it’s a week later that I’ll start to emerge and check in with my management and be like, ‘Everything good?’ She still hasn’t listened to her album yet, but what she does enjoy is hearing other people’s experiences of it and understanding that that’s never going to be something that any artist can control when their work is released in the world. “It’s about their experience now, not mine.”

Before we started our interview, I managed to catch a video of Isobel recording with some cardboard, so it felt only right that I ask about her studio space, a place where she spends most of her time. Walk into her studio, and you’ll find two pianos, each serving a different purpose. The upright has its entire front panel removed, and the top is filled with random items used to prepare the instrument. And then there’s the baby grand, by contrast, which remains pure. She shares more in-depth about how she enjoys finding time to create sounds for her music, “part of building a world is trying to create something that doesn’t feel recognisable. I really like starting a project by making sounds that feel like it’s curated for the thing that I’m working on.”

For Munich – The Edge of War, a film about the haunting legacy of war, she went to a junkyard and collected materials. “I wanted it to feel like shrapnel, or a sort of tinnitus kind of thing.” For other projects, she’s used bouncy balls and recorded them bouncing down a hallway. The experimentation isn’t just about finding unusual sounds; it’s a tool that breaks her out of the day, out of any working patterns that might be building up subconsciously. “Right at the beginning, when you don’t really know what it is, I feel like there’s a process where you have to let go or undo everything else in the day. And that sometimes can only really happen with quite extreme experimentation.”

Last year saw Waller-Bridge covering multiple disciplines—stage, screen, and her own music. That investment in herself has become how directors discover her. "I love it when somebody finds my music from a record rather than from a score. It's a fun way to find a composer." It makes sense. Her records are pure expressions of her own voice, while scores are collaborative by nature. "A lot of the time, people are like, 'What's your sound?' I never like to repeat a score because they're not always mine—they're collaborative, they're somebody else's vision."

When she’s not composing, shes deliberately not listening to music, at least not music similar to what she makes. Right now, it’s throat singers, audiobooks, and podcasts. When she does return to music, it’s to the things that shaped her time growing up, the Beach Boys, Pergolesi's Stabat Mater, ANOHNI and the Johnsons, Morricone, and Badalamenti's work with David Lynch. "David Lynch's films are so important to me. I find them so rich and delicious."

Looking ahead to 2026, she’s working on projects that she can’t yet discuss, but she’s also carving out space for simpler pursuits. Travel to Norway or Patagonia, “a big horse ride, just a week of trekking.” Reading, she’s determined to finish Red Comet, the Sylvia Plath biography she’s been working through. They’re modest ambitions from someone whose work is so expansive, but maybe that’s the point. After years of “going so hard on everything,” she’s learned the real luxury is time. Time walk, to think, to disappear into the dark of her studio and emerge with something that feels true.