The Brontë Sound That Modern Cinema Keeps Recreating

From Newman to Sakamoto, cinema keeps returning to Brontë country, and so do its composers.

With the newest addition of Emerald Fennell’s Wuthering Heights now out in cinemas with a score done by Anthony Willis, it feels like as good a moment as any to ask the question that serious film music listeners have been quietly asking for decades: why do filmmakers keep coming back to the Brontës, and what exactly are they hoping a composer will solve for them? These are novels that resist easy translation, too wild, too morally unresolved, too invested in weather as an emotional state. And yet Hollywood, European cinema, and even prestige television have never been able to leave them alone. What follows is a look at five composers we’ve picked who took on that brief across eight decades, each of them arriving at the moors with a different set of tools and a different idea of what the story was actually about. The results say as much about the moment they were made as the source material they were drawn from.

Alfred Newman – Wuthering Heights (1939)

Newman arrived at the Brontë moors the way Hollywood always did in its golden era: with a full orchestra and not a single second thought. His score for William Wyler’s Wuthering Heights is unashamedly lush, built on a sweeping main theme that became so associated with doomed romance it practically invented the template. What’s interesting is how little it actually sounds like a novel. Brontë’s Heathcliff is feral, violent, borderline sociopathic, but Newman’s music makes you believe in a love story anyway. That’s the trick. The romanticism isn’t illustrating the text so much as overwriting it, softening the brutality into something a 1939 audience could weep over on a Saturday afternoon. It won him an Oscar nomination and set a standard, or maybe a trap, that every composer after him has had to reckon with.

John Williams — Jane Eyre (1982)

This is the John Williams most people have never heard, and in some ways, the most interesting one. Made for the Franco Zeffirelli television adaptation, the score sits in a quieter register than almost anything else in his catalogue, no brass fanfares, no mythic swell. What he gives Jane Eyre instead is something closer to restraint: piano-forward themes, a certain muted melancholy that suits a woman who has learned, very young, to keep her feelings below the surface. It sounds, at points, almost tentative. Whether that's a conscious choice or a function of the format (television budgets were not Star Wars budgets) is hard to say, but the effect is oddly right for a story about interiority. Jane Eyre has always been a novel about what is not said out loud, and Williams, perhaps unwittingly, scores exactly that.

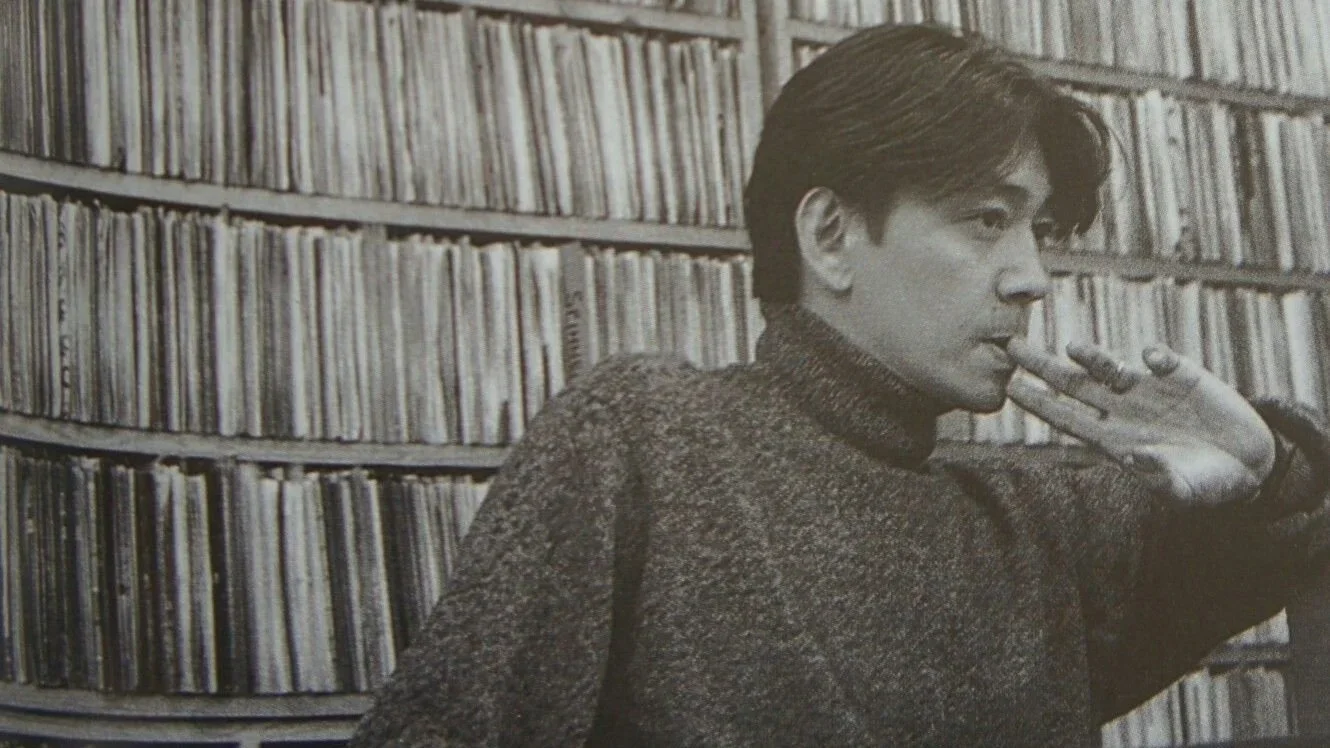

Ryuichi Sakamoto — Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights (1992)

Sakamoto didn't try to decode Wuthering Heights so much as to approach it from an oblique angle, which, if you know anything about the novel, is probably the only honest approach. His score for the Peter Kosminsky adaptation resists the orchestral grandeur that Newman established, trading it for something more atmospheric, more considered, with that characteristic Sakamoto quality of making space feel inhabited. Some passages sound almost liturgical, others that are barely there at all. He seemed less interested in scoring the passion than in scoring the landscape, the moors as psychological state rather than a backdrop. Coming off The Last Emperor and Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, this was Sakamoto in a more reductive mode, and the restraint feels earned rather than minimalist for its own sake.

Dario Marianelli — Jane Eyre (2011)

Marianelli had already done this once, more or less, his Pride & Prejudice score in 2005 redefined what a literary adaptation soundtrack could sound like, intimate and piano-driven in a way that felt genuinely new at the time. For Cary Fukunaga's Jane Eyre, he returned to similar territory but darker, the piano still central but now shadowed by strings that don't resolve where you expect them to. It's a score that understands Brontë's novel as a gothic work first and a romance second, the tension between Jane's rational control and Rochester's chaos is built into the harmonic language itself. There's a sophistication to how Marianelli handles the film's silences; he knows when to stop. It won't dislodge his Atonement work from the conversation, but it may be the more precise piece of writing.

Abel Korzeniowski — Emily (2022)

Korzeniowski has built something of a career out of neo-romantic maximalism, Romeo & Juliet, W.E., Penny Dreadful, and Frances O'Connor's imagined portrait of Emily Brontë plays to every one of his instincts. The score is unabashedly gothic, string-heavy, with a melodic sensibility that leans into the mythologising the film is openly engaged in. This is Emily Brontë as doomed artist, as visionary outsider, and Korzeniowski scores her accordingly, not as a historical figure but as the protagonist of her own novel. It's a score that wears its influences on its sleeve, Newman included, but earns that lineage by taking the emotional register seriously rather than ironically. Whether you find it overwrought probably depends on how you feel about the film's central argument, which is that the woman who wrote Wuthering Heights must herself have been Wuthering Heights.