The Composer of Wuthering Heights on Emerald Fennell, Film Music, and Why Less Isn't Always More

Anthony Willis has scored every film Emerald Fennell has ever made. Here, he reflects on creative instinct, the art of restraint, and what it really takes to score a film.

Words by The Blank Mag

There are film composers whose work disappears into the fabric of a scene, and there are film composers whose work you find yourself returning to. Anthony Willis is firmly the latter. His scores have a quality that is becoming increasingly rare: they are genuinely beautiful to listen to. The kind of music that feels orchestral in the fullest sense of the word: modern and unhurried, and built to last.

Willis grew up in London, sang at St George’s Chapel in Windsor, and trained at the University of Southern California, where he eventually found himself working alongside John Powell, composer of the Bourne films, Shrek, and How to Train Your Dragon. It was Powell, Willis has said, who changed his life, telling him to take on composing full-time. He listened. His credits since have included How to Train Your Dragon 2, Promising Young Woman, Solo: A Star Wars Story, and The Outfit, among others.

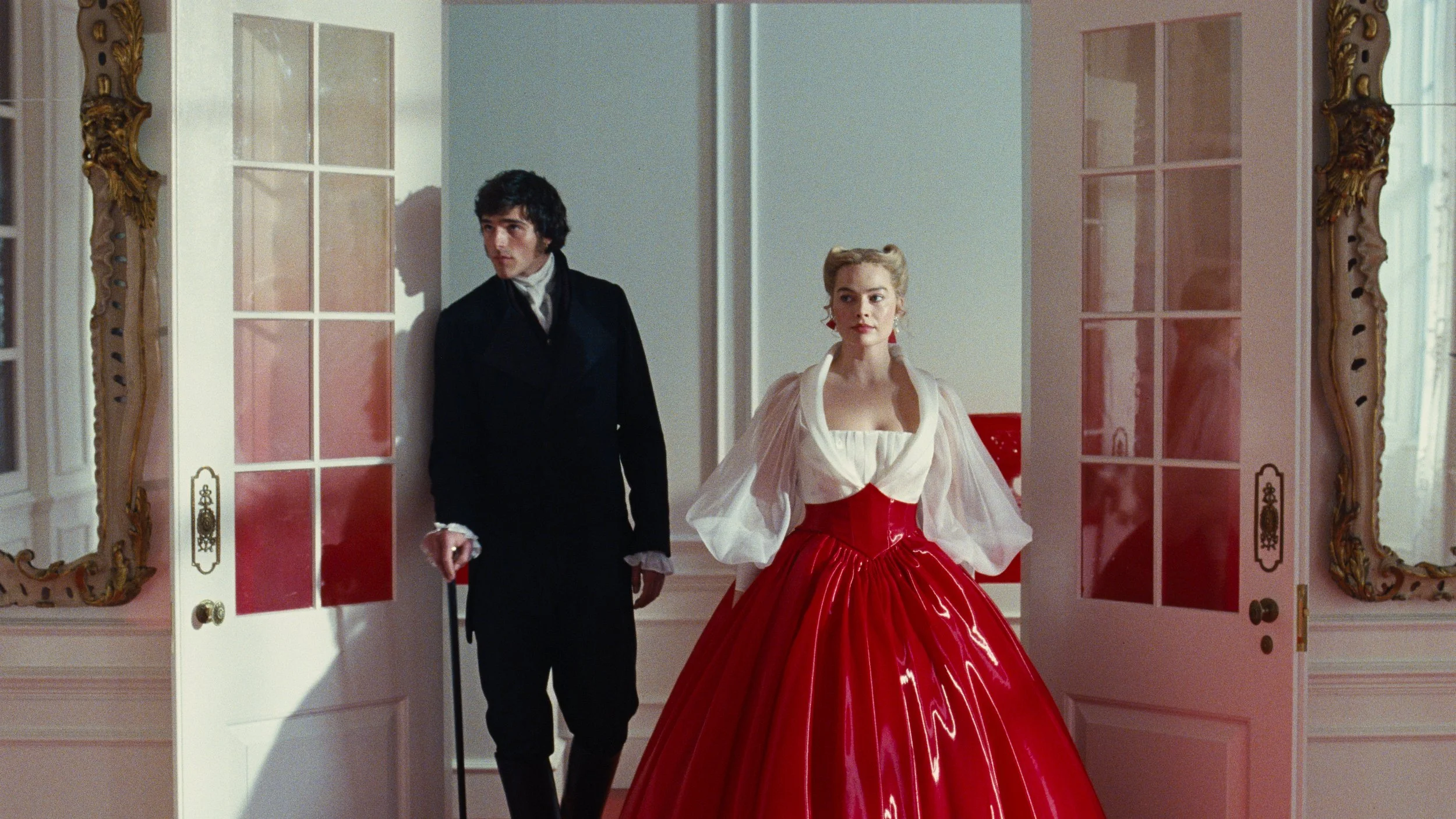

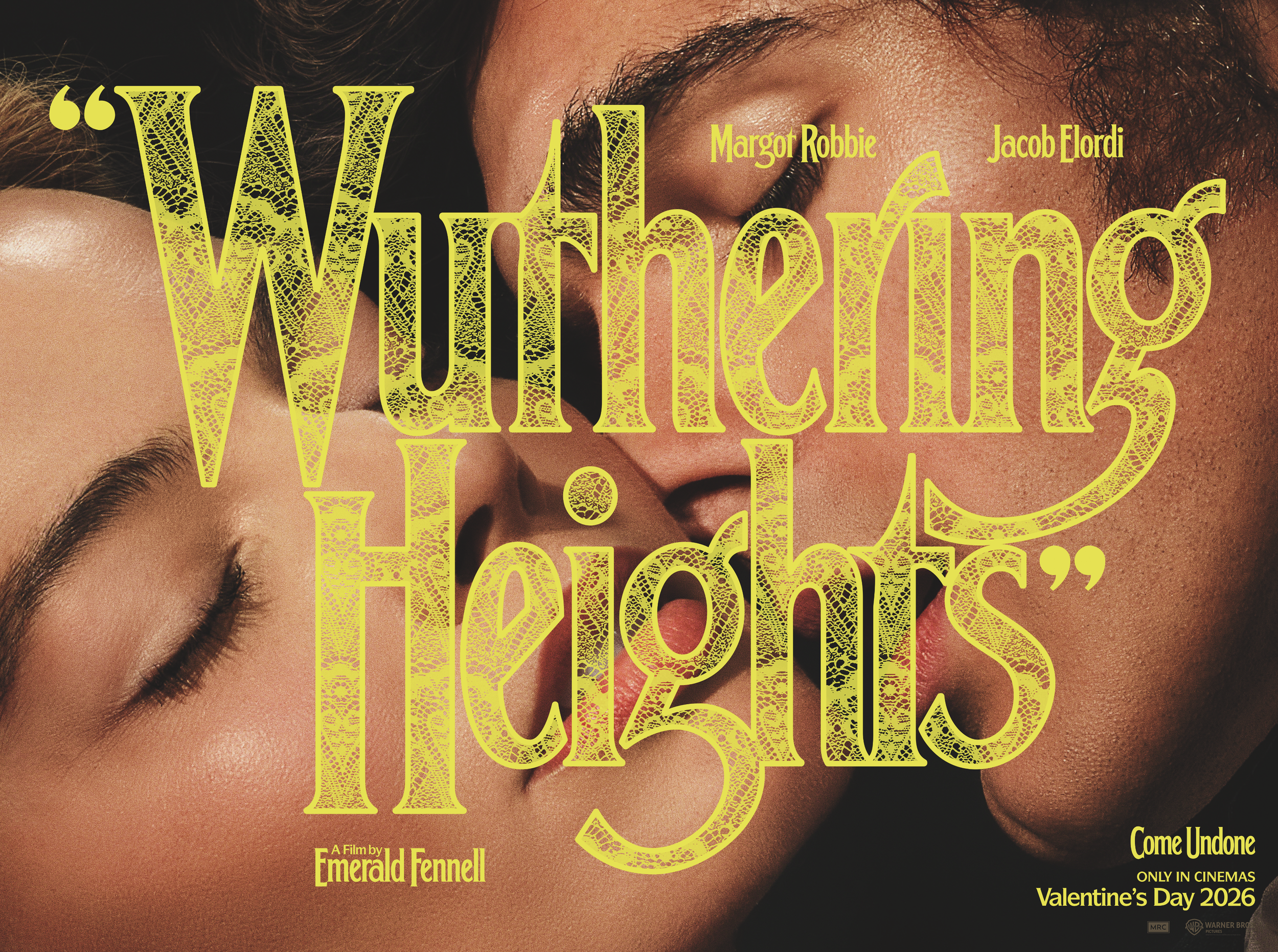

But it's his ongoing collaboration with director Emerald Fennell that has come to define this particular chapter. Willis has scored all three of her feature films, Promising Young Woman, Saltburn, and now Wuthering Heights, each time finding a different emotional register entirely. Wuthering Heights opened to $83 million globally in its first weekend, number one at the box office on both sides of the Atlantic, with audiences turning out in force despite a divided critical reception. Willis's score sits at the heart of it. We spoke to him in a brief window between projects.

What's a piece of music from your childhood that you didn't perhaps understand but has maybe helped shape how you compose now?

That's a really great question. I often think about music that, when I was younger, used to really amaze me in terms of how it was put together. And now, as a composer, I understand it a little bit better; I can see behind the magic of it. So I wonder if it has the effect that I thought it did when I was younger. There's this question: as composers, how do we retain the magic that music has on us? Because by default, we have to become so obsessive in terms of how we get under the hood with it. How do we retain that honest, innocent reaction to it that we had when we were younger?

There's a lot of music I didn't understand at all how to make, and now I have a better understanding of it. I remember when I was younger, I'd hear music and go, "God, that's a bit full-on, don't really get that." And now I listen to it, I'm like, "What do you mean? That's easy on the ears." Similar to our taste palettes with food, they mature. We can handle more complicated harmony.

“ I really like to have time with the film just to react to the photography. I think that's really important.”

When has a director or collaborator completely changed your initial instinct on a scene, and were they right?

Absolutely. There's a track in Saltburn that speaks to this question of how much the tone of the score in a film foreshadows darkness even when it's ahead of the story. Often, you'll see a dark movie where it's not dark yet, but the score will already be kind of setting the scene that something's dark.

In Saltburn, the wonderful editor had put in something for the friendship montage between Felix and Oliver; it was cool, but it was quite dark. It suggested this friendship was heading somewhere a little dark. And Emerald was like, "No, no, no. This just needs to be like they're having the best time and they're connecting in the most, this is euphoric." That track turned out to be Felix Amica, which became a very popular track. So she really made me realise what she wanted to do with it. It's that question of whether you're doing a more macro tone for a score versus being in the moment.

What's the most honest piece of music you've ever written, and why did that project unlock it?

With Wuthering Heights, the love story, what Emerald really wanted to do was capture this sense of innocence in children. Although, of course, historically, Wuthering Heights and the way it's scored has a sort of more Gothic, lightning bolt, thunder and lightning tone to it, what Emerald was really looking for was this very plaintive, restrained, honest yearning. This optimism in the story is that they might be together. By the end of the movie, you find out they're really just both together and apart, if that makes sense.

Some of the music in Wuthering Heights has been awesome to get reactions over the weekend from people really feeling that landing. It's quite a simple score, but I think it's quite present. It's getting under people's skin. The theme almost plays like a hymn. It's a sort of English folk hymn where they're bonded together as children, and it's throughout the movie. Sometimes we just reduce it to the simplest of the chords around it, but what's nice is I think it still retains its personality. Yes, I think it is very honest.

Do you think film music should be noticed or should it disappear? Where do you stand in that debate?

That is such a good question. The word "noticed" is a really tough one, being conscious of something. I've experienced it myself when I've tried to reduce and reduce a cue, and eventually the problem with that is the more minimal the music becomes, the harder it is to envelop the narrative in it. If there's very little body to it, an introduction of a new narrative colour is going to stick out hugely. So actually, it's counterintuitive, if you try to make the music too reductive, the noticeability of it can increase, in my opinion.

What's so great about the orchestra is that if there's enough body to it, then you can introduce colours that will feel seamless. My experience is you kind of need to put a stake in the ground and say, "This is my intention," and then it has a weird way of being unnoticeable because it feels right. When it feels right, it integrates. When it's too reductive, too boring, audiences are used to listening to really good music. When you do things that fall short of what makes music work well independently from a film, I think it can wear on an audience.

If your music had a blind spot, perhaps something you avoid or struggle with, what would it be?

Any composer who doesn't have a blind spot is lying. I think our blind spots obviously have a relationship with our comfort zones. When we all started doing this, we didn't have any comfort zone. I try to remind myself of that a lot. It's also this question of sometimes defining yourself as an artist based on what you like to do and what you don't like to do. But I always have to remember that there was a time I didn't do any of those things at all.

I like to think that wherever you go, that taste will still be there. I see that in the composers that I really love and admire, their way of applying that, honestly, I think it would be the same if they decided to write a poem. You'd see that same personality.

One thing I do grapple with sometimes is energy, actually. Tempo is really tricky because it doesn't want to overpush, but it doesn't want to be under. It's finding that sweet spot, and it's often related to the broadness of the arrangement as well. Energy, it's a very special thing, how we derive a piece of music being energetic. With film music especially, something feels really fast, and then you take it away, put it in another scene, and it doesn't feel fast anymore.

“What's so great about the orchestra is that if there's enough body to it, then you can introduce colours that will feel seamless.”

What do composers need to feel like they are doing their best work?

I think we're often not asked that. We are service providers, and we don't dictate schedules. It's probably a good thing we don't dictate schedules, or we would never finish our scores. But for me, I really like the time with the film just to react to the photography. I think that's really important.

What's the first film where you really noticed the soundtrack?

On a deep emotional level, The Lion King. I was actually just watching it with my oldest son this morning. It's just so good and out of this world. It's definitely one of the first films I saw when I was younger, and I saw it exactly as you're supposed to see it: as a completely cohesive experience.

But the first score album I owned was Titanic. I used to play it all the time. I built a model ship and would play the leaving port cue ‘Take Her to Sea’, ‘Mr. Murdoch’ and I would simulate the ship leaving with the blast on this crappy old CD player. I sat at my piano and worked it out. James Horner, it was phenomenal.